Portraits

Portraits are images of people who lived or once lived. As such, portraits tell us rich and intimate stories about individuals. They bear witness to how people lived and what they cared about in their societies, families, and personal identities. On the surface, a portrait might speak to a person’s professional role, express a singular emotion, or capture a unique personality. But portraits also reveal – sometimes inadvertently – the embedded expectations of a society. Portraits tell us not only what was important to the sitter but also what artists and audiences knew and understood about their societies.

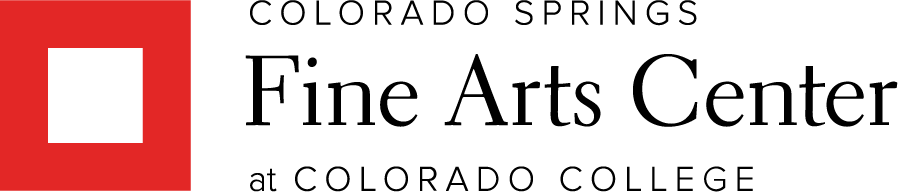

The FAC Museum collection contains many examples of portraits; a high percentage are art works made by artists who either lived or were active in this region of the American West. This selection of portraits from the late 1800s to the late 1900s encompasses a variety of media and a wide range of individuals. Most portraits in this group were made by white men for white audiences. As documents of societal structures, these portraits also bear witness to truths in American history and society about status, power, and oppression based on class, gender, and race. Note several depictions of Indigenous people by white artists such as Bert Phillips, Artus van Briggle, Gene Kloss, Edward Hopper, and Charles Craig. These images reflect racist and colonizing attitudes by representing Indigenous people as anonymous figures, as ethnographic types, or romanticized characters. The portraits objectify the person and deny their agency as individuals. Compare such disempowered subjects to the assertive stances and direct gazes given to representations of white men, by Hans Papp and Bernard Arnest, for example.

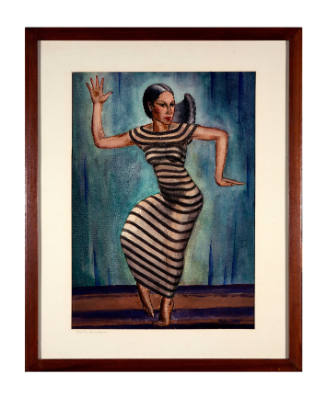

Consider also the portrait of Frank Loper (1850-1937) by George Biddle. Biddle was a renowned muralist from a wealthy and politically well-connected Philadelphia family. Trained as a lawyer, Biddle learned painting in France and Mexico, where he worked with the muralist Diego Rivera. Drawing on his admiration for the state-funded arts program in Mexico, and through his friendship with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Biddle helped create the Federal Art Project in 1935. This program employed artists during the Great Depression under the Works Progress Administration. Biddle may have met Loper at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, where Biddle began teaching in 1937. It is not known who commissioned the portrait, or where it originally hung.

Biddle's portrait shows Loper in a tuxedo and white gloves standing next to a chest. The pose, costume, and stance identify him as a servant, probably in his role as butler to the Hayes family. However, the portrait erases Loper’s many life accomplishments and his leadership within the African-American community in Colorado Springs. Born an enslaved person on Jefferson Davis’ Mississippi plantation, Loper came to Colorado Springs in 1886. He worked for Davis’ daughter Margaret Davis Hayes, at the Antlers Hotel, and at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Loper married Maude Gray Macon, a grand-niece of Frederick Douglass, and together they raised Frederick J. Macon, later a Tuskegee Airman. Loper was the president of the Antlers Publishing Company, which between 1897 and 1905 published the Colorado Springs Sun, the first paper in the city intended for Black audiences. In 1903, along with other previously enslaved persons, Loper founded the People’s Methodist Episcopal Church, which continues to serve Black communities in Colorado Springs. For more on Frank Loper, see Pikes’ Peak Library District archives and Franklin J. Macon’s memoir, I Wanted to Be a Pilot (2018).

Reflecting on the inspirational life story of Frank Loper, which differs so dramatically from Biddle’s blank, even servile, portrait, we can see how portraits do not offer straightforward truths. A portrait is always nuanced, mediated, relative, and situational. As documents of the lived experience of others, portraits inspire empathy and contemplation. But as witnesses to societal structures, portraits also can reveal the darker histories (such as slavery, settler colonialism, and sexism) and painful struggles for justice that continue within our communities and nation.